- Home

- Polly Crosby

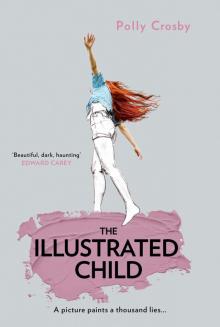

The Illustrated Child Page 2

The Illustrated Child Read online

Page 2

I came to a stop at the water butt that stood under the guttering. Mouldy snails floated in the water, covered in a film of green slime and exuding a smell like rotten cucumbers. I held the nail varnish above the water, poised to drop it, mesmerised by the smooth khaki surface. But then a particularly bulbous snail floated past, putrid and engorged with slime, and I changed my mind and dropped down on my knees to look underneath instead.

Here, the grass had grown strong and lush from the constant drip of fetid water, and I crouched down and placed the little bottle there, plaiting the blades over it to hide it completely. I sat back on my haunches and studied the effect.

‘What are you doing?’

At first I couldn’t locate the voice. For a moment I thought it might be the buddleia tree that covered half the cart shed, its branches gesticulating gently in the breeze. I stood up.

‘Who’s there?’

‘What were you doing?’ The voice was more insistent now. It was definitely coming from the buddleia. I looked carefully between the branches. A mop of tawny hair and two eyes were peeping over the wall behind the tree. I flushed.

‘Nothing.’

‘Didn’t look like nothing.’

‘It was nothing to do with you.’

‘Didn’t say it was. It looked like fun, that’s all.’ The eyes and hair disappeared. I waited for them to reappear, but they didn’t. Worried I’d upset this new-found being, I ran to the gate to get a better look.

‘Hello?’ I asked desperately, peering through the wooden slats. The mop of hair appeared, this time attached to a muddy T-shirt and shorts, and two stumpy legs.

‘You look like an animal at the zoo,’ it said, ‘can I feed you?’

‘You don’t know what I eat.’

The stranger put a hand in a pocket and pulled out a worm. It dangled there, trying to turn up towards the sky. ‘These?’

I backed away. The stranger grinned, throwing the worm on the ground.

‘Want to play?’

My stomach contracted. I took in the muddy clothes and a nasty-looking graze to the cheek.

‘Yeah,’ I whispered in awe.

Stacey was a girl. I hadn’t been sure at first. Her hair was short and messy. It hung down at the front like two curtains over her eyes. ‘His eyes,’ I whispered, thinking she might have lied and she really was a boy. I wondered how I could check. She had very straight teeth and marks on her cheeks that could be freckles like mine, but were more likely dirt.

We were walking down an overgrown path that Stacey said led to a river. I had never been this way before. I thought back to the water butt and the nail varnish hidden underneath it. I wondered if Stacey had seen me hide it. I opened my mouth to confide, but stopped myself. Perhaps I should wait a while: I would tell her if we were still friends tomorrow.

‘Here, want one?’ Stacey said, offering me a sweet from a little foil packet.

‘Thanks.’ I popped it in my mouth, and my lips crinkled at the perfumed taste. I shivered and swallowed quickly, picking the remains out of my teeth.

Stacey was beating the nettles down on either side of the path with a stick. She stopped abruptly and pointed to a giant stinger on our left.

‘I dare you to pick it,’ she said.

‘No.’

‘Go on.’

‘No.’ I twisted my fingers into the hem of my jumper. I didn’t like this game. It felt dangerous.

‘Fine. I will.’ And she bent forward and picked it.

‘Didn’t that hurt?’ I said, my fingers contracting in empathy. She dropped the nettle and looked at me sympathetically.

‘Watch what I do,’ she said, a smile playing around the corners of her mouth. She moved her hand towards another nettle, and just as she got to it, she placed her thumb and index finger on the underside of the two lowest leaves. Pushing up, she clamped the leaves to the stalk and pulled. The whole nettle uprooted itself and hung from her fingers.

‘Ha!’ she cried, swinging the plant to and fro and looking at my uncomprehending face. ‘The underside doesn’t have prickles. Here.’ She proffered the nettle to me. I took a step back. ‘Fine. Come on, let’s go.’ Dropping the nettle, she pranced away.

I watched her running, a flush of admiration crossing my face. Setting off after her, I mounted some concrete steps that led to the river.

At the top I stopped. Stacey was already at the bottom, making her way toward the water’s edge. I turned and looked back at Braër. I had never been out of the garden before. Not without Dad. My hand went to the mole on my cheek, stroking it distractedly.

‘Stacey!’

She turned and raised her eyebrows. Her upturned nose was pink.

‘I don’t think I’m allowed to go any further.’ As I said the words, I felt shame in my tummy. It made me want to go to the loo.

‘Well, I’m going to look for buried treasure under the bridge.’ And with that she turned and skipped towards the water.

I took a deep breath and gripped the railing. Slowly, step by step, I started to descend the concrete steps. Every second I expected Dad to come running up behind me, asking me what on earth I thought I was doing, but he didn’t. Letting go of the rail, I ran down the remaining steps and joined Stacey at the water’s edge.

She was staring into the grey depths below. The heat of a late spring had dried the banks, and the water had slunk back to reveal foul-smelling mud on either side. We made our way to the bridge, and Stacey started climbing down the bank, gripping handfuls of marram grass as she went. I looked at my shoes. They were my favourites: plastic trainers with planets dotted all over them. I took a deep breath and followed her.

Stacey was already under the bridge when I reached the muddy bottom. I had to duck to join her in the shadows. A thrill rushed through me as I straightened up under the planks of wood. The river made a roaring sound here as it channelled under the bridge. It looked a lot more powerful close up.

My trainers were sinking into the mud. Every few seconds I had to pull my feet out. The mud made a sucking sound, and a great gassy waft hit me in the face. The planks of wood that made up the bridge above us echoed dully as someone walked across them. Grains of dust fell down onto us.

Stacey was scanning the ground, her eyes bright, her hair tucked behind her ears. Then, she dropped down, her fingers slipping into the mud and withdrawing just as quickly.

When she straightened up, there was a small grey pebble in her hand. The excitement I had felt when she first dived in died at the sight of it.

‘It’s a stone.’ I couldn’t keep the disappointment out of my voice. Stacey glanced at me, her eyes glinting in the dark shadows, but kept silent. Pocketing the stone, she continued to look at the ground.

I pulled my feet out of the mud with a slurping sound, and, ducking out from under the bridge, made my way up the bank, wiping dust from my face and clinging to the marram grass to help me up.

When I was at the top I sat down to wait for Stacey. I looked about for the person who had walked across the bridge, but the land was flat and empty as far as I could see.

‘Stacey,’ I called nervously. Her earthy face appeared below me. One strand of hair was slicked with mud.

‘What?’ she asked, tucking the muddy lock of hair behind her ear and sniffing noisily.

‘That person that walked over the bridge just now. There’s no one out here.’

Stacey grinned. She climbed out and joined me on the bank, wiping her shoes on the grass to remove the clumps of mud. ‘Happens a lot round here. Some say there’s a man lurks near the river, waiting for little girls to kidnap.’ She put her hand in her pocket and pulled out the pebble. ‘Here,’ she said, handing it to me.

I took it. It was lighter than I thought it was going to be. The surface was smooth and greasy. I rubbed it between my hands. It began to crumble. Stacey leant toward me.

‘I wonder who dropped it?’ she whispered. I could feel the ends of her hair tickling my ear. I rubbed harder at the pebb

le. It started to break into pieces, disintegrating beneath my fingers. That same putrid vegetable smell hit my nose. It was made of mud, but there was something hard beneath. My tummy twitched as a flat surface met my thumb. A little brooch, its pin long since lost, fell onto my lap, brown and rusty, but solid and round.

‘Buried treasure,’ Stacey said.

‘It’s like magic,’ I said, ‘ghost magic.’

Stacey nodded, her face serious, staring out at the flat fields that surrounded us.

‘You need to see the shrieking pits. That’s proper ghost magic.’ She leant back on her elbows and raised her eyebrows, waiting for my reply, knowing it was coming.

‘What’s the shrieking pits?’ I asked obediently in a whisper. The grey sky dropped lower on the landscape as if it were listening too.

She leant in to me and looked me in the eyes. I noticed her left eye had a dark grey slash across its green iris. ‘No one knows why they’re there. Some say they’re millions of years old, ancient holes that have filled up with rainwater. Others say they were dug a hundred years ago: people quarrying for rocks and flint. But sometimes, weird noises come from them. Screams and cries for help. And people see things when they’re near them.’

‘Things?’ I murmured, almost not wanting to hear her answer. I was beginning to regret my trip to the river.

‘People. Acting weird. Ladies dressed in old-fashioned clothes.’

‘Have you seen them?’ I held my breath, my body stiff, waiting for her answer.

‘Nah. I don’t even know where they are. We should go looking sometime.’

I scratched at the brooch in my fingers, relieved. Flakes of metallic mud fell away. It was pretty, about the size of a pound coin, with a frilly edge and lots of little decorative holes dotted about it, like a doily.

‘I think I’m going to like living here,’ I said.

‘Where did you live before?’

‘Dad and me moved around a lot. Before we moved to Braër we were staying in a B and B. And we camped, too.’ I had a vague memory of a caravan and strange-smelling tea. ‘Before all that we used to live with my mum in London.’ I scratched my finger into the muddy ground. ‘But she went away.’

‘It must be weird, not living with your mum anymore.’

I hadn’t thought about it before. I rarely thought about Mum. It was years since I last saw her, she was so far back in my past that weeks could go by without me remembering her at all. Now with Stacey’s question, a guilty feeling opened up inside my chest.

‘Why did she go away?’ Stacey said.

‘I don’t know.’ I put my eye to the holes in the brooch. The world was fragmented, like looking through a thousand keyholes, and I could only see a tiny part of everything so that I couldn’t work out what it was I was looking at.

‘My dad went away,’ said Stacey, ‘I don’t see him often, maybe five times since I was a baby.’

‘That must be strange.’ I couldn’t imagine not having a dad.

‘It’s OK. I sort of do have a dad sometimes. It depends who Mum brings home. Sometimes, if I don’t want to go home, I go to my gran’s instead, and sometimes I just stay out here.’ She gestured to the flat fields that surrounded us.

‘What, even at night?’

Stacey shrugged. ‘Sometimes. Do you still see your mum?’

I shook my head. I tried to picture what she looked like, but all I could see when I screwed my eyes up was a pair of smooth, delicate hands holding onto mine, sharp red nails gripping my skin painfully, a glittering diamond ring crackling with light.

‘I haven’t seen her since we left London,’ I said, ‘and that was when I was four.’

‘Is she still in London?’

‘I’m not sure.’ I tried to remember if Dad had ever told me. ‘I think she might have left to join the circus,’ I said, thinking about a painting Dad was working on at the moment: sequins and colourful feathers and soft, wavy chestnut hair. I had glimpsed it earlier, walking past Dad’s study, but he had kicked the door shut before I could see anything more.

‘Cool,’ said Stacey, ‘imagine being with lions and elephants every day.’ She pulled at the marram grass. ‘I’d love to go to the circus,’ she said wistfully, ‘but Mum never goes anywhere. She just sits at home, watching TV.’

‘Where do you live?’

‘On the other side of the village. You know the long road that leads out towards town?’

I nodded, remembering an ugly line of boxy houses we’d driven past when we moved here.

‘I live over that way in a little red-brick house.’

It sounded like something out of a fairy tale. I imagined her and her mother, welcoming different dads inside, plying them with mugs of tea and cuddles.

‘What was your house in London like?’ she said. ‘Was it big and spooky, like Braër?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know much, do you?’

‘It must have been quite big, because there were more people living in it.’ I had a hazy memory of closing my bedroom door so that I could sit still and quiet and alone in the small space. It was a busy house where I never had a moment to myself. There was always raucous laughter, occasional yelling. Sometimes there were smacks followed by kisses to take the pain away. ‘It was very different to Braër,’ I said.

Stacey got up from the bank, brushing the dirt from her shorts. I started to hand the brooch to her.

‘No, you keep it, it’ll bring you luck,’ she said. ‘People lose things all the time, make sure you don’t lose it.’ She smiled. She had a pretty smile. It transformed her face.

‘You look like a girl now,’ I said.

She laughed. ‘That’s why I don’t smile very often. I wish I was a boy sometimes.’

‘Why?’

She kicked at the grass. ‘I don’t know. Boys have it easy. They fight better.’

I glanced at the sky. Behind the low clouds the sun had begun to peer out. We were both squinting in the hazy light.

‘I’d better go home,’ Stacey said with a sigh. ‘Can we play again?’ I nodded, squeezing the brooch in my hand.

‘Right ho. See you, wouldn’t want to be you!’ She grinned at me, and then she was off, running across the grass.

I watched her go, jealous of the speed at which she could run, then looked at the watch on my wrist and wished it was more than a plastic toy. Dad would be frantic. I started on my way home, the mud on my trainers weighing me down like an astronaut with moonboots.

Three

I wanted to see Stacey again, but every time I thought about climbing the gate and going looking for her, I felt a sick feeling clenching in the pit of my stomach. Dad hadn’t mentioned my mud-encrusted trainers, but they appeared on the washing line the next day, clean and sopping, with muddy drips leaking from the ends of the laces. They took three whole days to dry.

It rained every day for the next week, and I spent my days inside, not daring to venture away from Braër on my own without Stacey.

But being inside meant I was in Dad’s line of sight more often. He followed me from room to room, drawing pad in hand, commanding me to stop while he quickly sketched in an outline. On a really wet Wednesday, when the rain was so torrential that the sound drummed into my skull, he managed to corner me, a comb replacing the usual pencil in his hand.

‘You really can’t carry on like this, Romilly. Your hair is so knotted it’s actually growing upwards.’ He pushed me onto a stool in the bathroom and set to with the comb, ignoring my gasps and winces as he attempted to tease out the knots.

‘Ow, Dad.’

‘I’m sorry, but we should never have let it get this bad. It’s like candyfloss, for goodness’ sake.’ He stopped, staring at my hair in the mirror. ‘There’s nothing for it,’ he said at last, ‘I’m going to have to get the scissors.’ He abandoned the comb, its teeth chewing at my hair, and went marching off.

‘No, Dad!’

‘I’m not going to cut it all off, I

just need to get rid of a tangle or two, that’s all.’

I looked in the mirror. He was right: I could see thick, matted areas that looked almost solid. There was a raven’s feather hanging from the back that I had stuck in there days ago. I tried to imagine myself with short hair. I thought about Stacey. She had short hair. It suited her.

When Dad came back, I said, ‘Does having short hair mean you turn into a boy?’

‘Not in the least.’

‘You can cut it off then. But keep the feather in it. I like it.’

When Dad let me go, my new haircut rustling around my ears, I roamed the house, turning my head this way and that, liking the way the air breathed on my exposed neck.

It was still raining outside, and I decided I would spend my time indoors wisely. Talking to Stacey at the bridge had brought to mind my mother, so I set out to discover as much as I could about her.

All of Braër’s rooms were accessible to me except one: Dad’s study, which was locked whenever he wasn’t inside. But Dad wasn’t very good at security, and he always hung the key on the wall next to the study door. Shaking my head at his lack of ingenuity, I unlocked the door and slipped inside.

This was his painting room. It was a small, square space that hung out over the moat at one end of the house. The walls were dark with mould where the damp had crept in, but the view made up for it: a huge picture window that looked out from the north end of the house towards a meandering stream. Dad had told me there was a watercress bed somewhere beyond the little bridge in the distance, and every time I ventured out that way, I picked a leaf from a different plant and tasted it, hoping for the peppery bite on my tongue.

I looked around the room, searching for vestiges of Mum that Dad might have brought with him: a pair of high-heeled shoes tucked away in a corner, or a pretty scarf hanging from a hook. There was a pair of shoes, half hidden under the cupboard near the window, but they were much too small to be my mother’s – something a little girl would wear, with large red bows at the toe. I picked them up and examined them, wondering if they had belonged to the same girl who owned the baby doll and the parasol. I turned to Dad’s desk, hoping for a letter from my mum, or else a paper knife, engraved ‘to darling Tobias, from your loving Meg’.

The Illustrated Child

The Illustrated Child